This article talks about some side effects. It explains why it is a bit suboptimal to distribute LilyPond snippets under the terms of the GPL. Even, if one loves to create, share, and/or use free and open-source software. And believe me, I do so. The side effect is simple. Including GPL-licensed LilyPond snippets enforce you to distribute your own work under the terms of the GPL:

Let us start with some hopefully indisputable points: The program ‘LilyPond’ is licensed under the GPLv3 [⇒ 1]. It wants “[…] (to create) beautiful sheet music”. [⇒ 2] For that purpose, the program LilyPond takes a file containing a music sheet represented in and by the LilyPond language. And based on this input file, LilyPond compiles the output:

LilyPond is a compiled system: it is run on a text file describing the music. The resulting output is viewed on-screen or printed. In some ways, LilyPond is more similar to a programming language than graphical score editing software. [⇒ 3]

Hence, the language LilyPond pretends for writing a music sheet is a programming language executed by the LilyPond interpreter. Writing music in and by LilyPond is software programming. In other words: LilyPond is a programming system like PHP‑, PYTHON‑, or BASH. The interpreter (the PHP‑, python‑, bash‑, or LilyPond engine) takes its input code and creates the corresponding, but new output. Such (open source based) engines are often licensed under different licenses than the code they execute. For example, PHP is licensed under the PHP license. But there exist many PHP programs licensed under the MIT, the BSD, or even under the LGPL license.

This holds also true for LilyPond — as the LilyPond repository proves. This repository contains … [⇒ 4]

- a file named COPYING which contains the text of the GPLv3 license.

- a file named LICENSE, stating that LilyPond falls under the terms of the GPLv3.

- a file named LICENSE.Documentation stating that all document input falls under the GNU Free Documentation License except the files in the directory snippets. They are public domain.

From these facts we can conclude:

- LilyPond itself is licensed under the terms of the GPL: You may run, study, modify and redistribute it. But in case of distributing a (modified) instance, you have also to distribute the License text, a list of the copyright owners, the source code and some other compliance artifacts — namely together with your instance.

- But the GPLv3 does not say anywhere, that the input files (e.g. the snippets, written in the LilyPond language) or the output files (pdf, png, …) have also to be distributed under the terms of GPLv3.

- Additionally, the LilyPond copyright holders DO NOT require anywhere that the input and output files also have to be released under the GPL (what they could have done, as for the example some code generators have done).

- Moreover, the LilyPond copyright owners know and accept that the LilyPond input (and output) files are not automatically be covered by the ‘strong copyleft effect’ of the GPL. Otherwise, they could not have embedded a set of snippets into their repository while stating that these are part of the public domain.

Hence, we may generally conclude that — from the viewpoint of LilyPond and its developers — the LilyPond input and output files may be licensed under other licenses than the interpreting program itself.

Consequently, we now should ask, which license the LilyPond snippet authors should choose. We see two role models:

- The first role model is the LilyPond Snippets Repository which hosts reusable snippets. In accordance to this LSR, all these snippets are public domain. [⇒ 5]

- The second model is the Open LilyPond Library. [⇒ 6] Its homepage is mostly a site skeleton. It only says that “openLilyLib is an enhancement library for the GNU LilyPond music notation software”. [⇒ 7 ] But if one takes a look at the GitHub repositories collected under openlilylib [⇒ 6], one finds the main repository “oll-core”, which introduces itself as “the heart of openLilyLib” and promises to provide common functionality that any ‘openLilyLib’ package uses. [⇒ 8]

Although this repository does not contain any file named COPYING (containing the GPL) or a file LICENSE or LICENSING, the header of the central source code file ‘package.ily’ clearly states, that “[…] openLilyLib is free software: you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the terms of the GNU General Public License”. [⇒ 9] This statement describes the will of developers (copyright owners) that each user of openlilylib has to respect.

But unfortunately the role model ‘GPLv3 licensed LilyPond snippets’ has some very unattractive consequences:

We know already, that the LilyPond snippet code itself is software. The command #include “ABC.ly” links a snippet into one’s own LilyPond music code. Or you copy the content of a snippet into your music code literally. Both modes of use trigger the strong copyleft effect of the GPL (v3 and v2): if my code functionally calls a method offered by a GPL-licensed snippet or if my code contains the GPL-licensed snippet literally, then my work depends on this GPL-licensed prework and I have to distribute my code also under the terms of the GPL, regardless whether I distribute it as source code or in form of compiled results.

Now, you might smell the rat: If I write my music by using the LilyPond description language and if I use any GPL-licensed snippet to do so, then I have to distribute my music under the terms of the GPL, namely the created pictures / pdfs as well as the code itself. Moreover, by distributing it under the GPL I grant anyone, who gets my results to use them, to study them, to modify them, and to redistribute them. And what does it mean to use music scores: Beside others, of course, to play the music.

Hence, using a GPL-licensed LilyPond snippet for creating your own music — regardless, of whether you use the include- or the copy & paste method — evokes that everyone who gets your work also and inherently gets the right to use it — for any purpose and without having to ask you again.

For being clear: Any author has the right to license his work under any license he likes. And the users of his work have to fulfill the requirements of the license he has chosen. No doubt. That’s the core of the Free Software World.

But what can those snippet developers do, who do not want to load such heavy consequences on their users?

- First, you might think that they could distribute their snippets/libs under the terms of the LGPL. [⇒ B] Then — due to the weak copyleft effect of the LGPL [⇒ B, §2/§4] — their users are free to distribute their own code/music under different conditions.

But that has also a — perhaps unwished — side effect: If I wrote a piece of music based on an LGPL licensed snippet, then I have to distribute together with my work the code of the snippet, the LGPL license text itself, a list of copyright owners [⇒ B, §4], and some other compliance artifacts. Distributing my work without these compliant artifacts would simply not be compliant. And for this it does not matter whether I distribute my work as Lilypond source code or binary pictures or pdfs!

- As a substitute, the snippet developers could explicitly state that distributing the music in the form of pictures / pdfs does NOT trigger the requirements of the LGPL.

Linking an open-source license with such an exception is a well-known practice. But using a really appropriate license is better than using an exception. Such a supplement states that the license text does not mean what it says.

- Third, they could license their LilyPond snippet under any other permissive open-source license.

But even these licenses enforce them to distribute compliance artifacts together with their music — in case of the Apache‑2.0 license, for example, the license text itself and the NOTICE file of their packages. [⇒ C §4]

- Finally, they could license the snippets/libs under the terms of one of the creative commons licenses [⇒ D]

By using the respective attributes they determine how the users shall show them respect (BY) and which additional requirements they have to fulfill [SA] or whether they do not have to fulfill any requirements [CC0]

- And very last they could shift their snippets into the public domain. In this case, they have to give up all copyrights.

The LSR chose this way to distribute the snippets. Unfortunately, this indeed does not hold for the European Legal Area: Here, we cannot give up our copyrights, we can only grant some of them to others: In Europe, there does not exist any ‘public domain’

Hence, what shall we do, if we — the snippet developers — want to support other musicians by simplifying their development work instead of burdening it by enforcing them to create some seldom recognized compliance artifacts?

- First, we can distribute our LilyPond snippets under the terms of the MIT license. This license is so small, that we can literally integrate it into our source code. Then, our source code contains already all artifacts the license requires: „The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software.“ [⇒ E]

- Second, we can distribute our snippets under the terms of a creative commons license. But only the CC0 does not impose our users anything. [⇒ F]

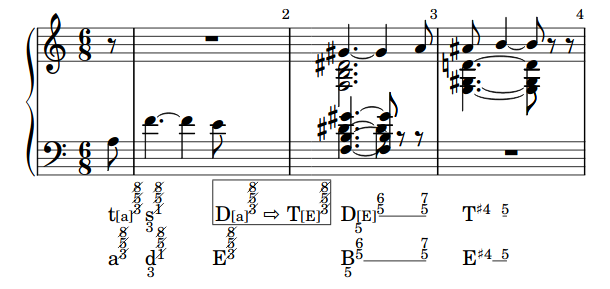

- Third, we can use the method of dual licensing — just as I did in the case of my snippet ‘harmonyli.ly’.

Yes, if we do so, we can no longer enforce, that our users share their improvements with the community. But let us be honest with ourselves: are our snippets so important, that we must protect their worth? I think, sometimes it is better to give without requiring a return. Our users often give us something back voluntarily.

And in what way is this …

… part of the overarching topic FOSS Compliance? For fulfilling the requirements of FOSS licenses, we have to consider specific individual cases as well as side effects — for software, pictures, or documents. We should unhide trends and write guidelines. Above all, however, we must drive forward the automation of license fulfillment, make our licensing knowledge freely available, cast it into smaller tools, and bring it into larger systems: Because FOSS thrives on freedom through license fulfillment, large and small. That’s what also this article is about.

- [1] http://LilyPond.org/gpl.html

- [2] http://LilyPond.org/introduction.html

- [3] http://LilyPond.org/text-input.html

- [4] https://github.com/LilyPond/LilyPond

- [5] http://lsr.di.unimi.it/LSR/html/whatsthis.html

- [6] https://github.com/openlilylib/

- [7] https://openlilylib.org/

- [8] https://github.com/openlilylib/oll-core

- [9] https://github.com/openlilylib/oll-core/blob/master/package.ily

- [A] https://opensource.org/licenses/GPL‑3.0

- [B] https://opensource.org/licenses/LGPL‑3.0

- [C] https://opensource.org/licenses/Apache‑2.0

- [D] https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/licensing-types-examples/

- [E] https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT

- [F] https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/